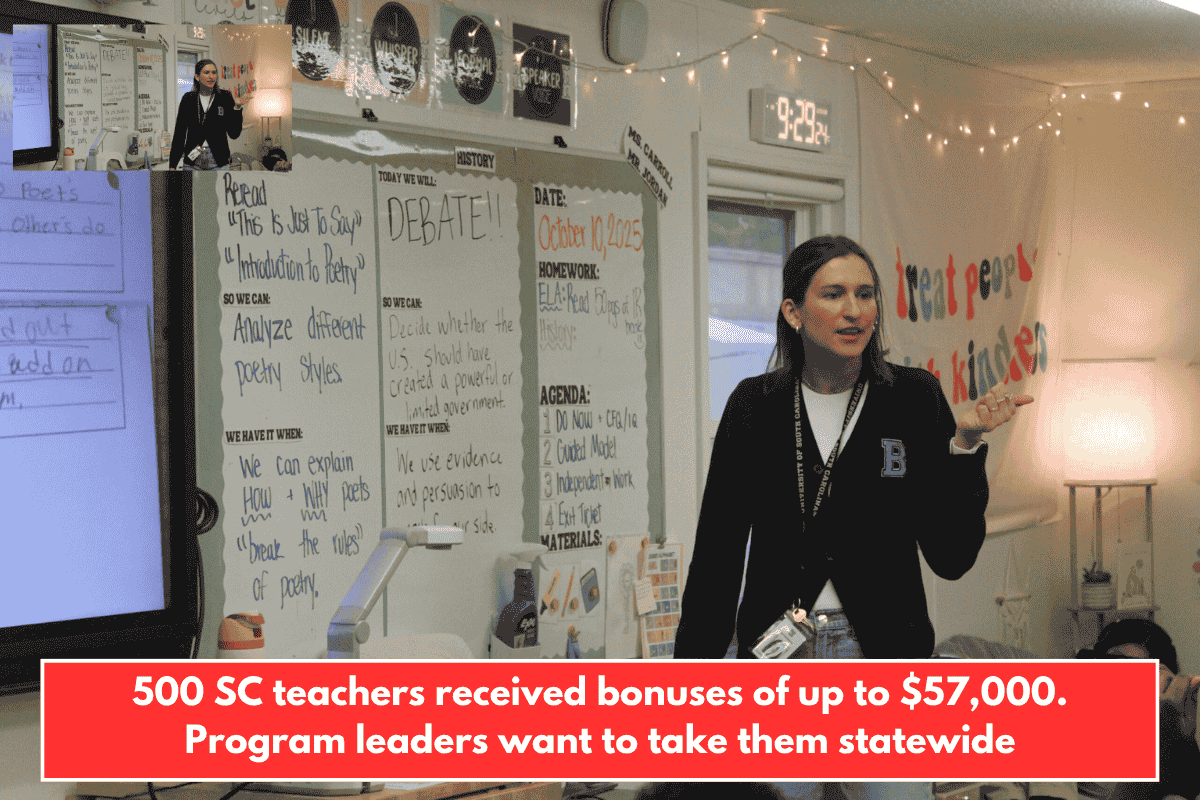

Sydney Carroll teaches an eighth-grade English lesson at Meeting Street Brentwood in North Charleston, South Carolina, on Friday, October 10, 2025. (Photo by Skylar Laird/South Carolina Daily Gazette)

North Charleston — A blue cutout that reads “100%” hangs on the wall in front of Sydney Carroll’s classroom.

The purpose is twofold: it’s a reminder to her eighth grade class that they should give their all to their classwork, but it’s also a reminder to herself because she’s aiming to have all of her students reading on grade level by the end of the year.

Carroll’s end-of-year incentive will increase as she moves more pupils toward that objective.

Carroll, who teaches English at Meeting Street’s Brentwood elementary and middle campuses, was among 526 teachers from 39 schools to earn an Excellence in Teaching Award this year. They totaled more than $4.6 million for kindergarten through eighth grade teachers whose pupils improved and demonstrated competency on end-of-year math and reading assessments.

The average award was $8,800, according to Beemok Education in Charleston, which manages the program for several of the schools.

Since its beginning in Charleston County in 2021, the pay-for-performance model has been adopted by dozens of schools. The program’s administrators see it as a means to recognize and retain the greatest teachers in the classroom. They want to see it expanded to include more schools, with a combination of private and public funding.

Carroll, who is in her sixth year of teaching, knew her pupils had done well previous year. She observed how hard they worked all year, and their end-of-year exam scores reflected it.

Carroll was surprised to receive a phone call informing her that she had received the year’s top honor. Her award is $57,250.

“I’m a teacher,” Carroll explained. “I’ve never heard that amount — or even close to it.”

She burst out crying as she heard the number.

She became accustomed to live paycheck to paycheck, rarely saving more than a few thousand dollars at a time. She stated that the single payment exceeded her annual wage for the first few years of teaching.

Her bonus exceeds the pay of many teachers throughout the state. This year, instructors can earn no less than $48,500. According to the state-paid compensation plan, teachers with a bachelor’s degree earn no more than $57,000 until their 18th year in the classroom, while districts sometimes pay more than the state minimums.

Carroll, a full-time graduate student, used the incentive to pay for a semester of school in cash, pay off debt, and save the remainder, she said.

She regarded the bonus as a reflection of the effort she put in to get her kids on grade level, which included early mornings rehearsing lesson ideas with principal Roger Michael and after-school grading sessions with friends.

When the school year began last year, only 7% of Carroll’s 75 kids, who were distributed across numerous courses throughout the day, were reading at an eighth grade level. By the end of the year, 45% were on grade level, with her children making an average of two years’ development.

‘What they deserved’

On a recent wet Friday, Carroll instructed her students to collect their pencils and face the front of the classroom.

“Alrighty, eighth grade,” Carroll began, beginning a reading assignment. Students looked up from the poems they were reading to see her.

“I love today,” Carroll continued. “It’s a challenge for us today, for sure, and that is OK, because that means we’re going to learn something.”

Fridays, particularly those with a difficult lesson leading into a four-day weekend, may be difficult, Carroll said. However, Carroll’s class stayed rapt as she exhibited one student’s responses to questions regarding William Carlos Williams’ poetry “This Is Just To Say,” a personal favorite of the teacher.

Carroll questioned her students: What exactly was Williams expressing in his poem? How did he alter the style? What might the reader learn?

Carroll did not provide the correct answers. Carroll toured the class during the two minutes allotted to eighth graders to read and evaluate a poem, asking struggling kids supplementary questions to help them think about the task differently.

Carroll refers to this as the “productive struggle,” and she believes it is what helps her kids achieve.

Reading, for them, is more than just reading the words on the page; it’s about continually thinking and asking oneself questions. Her lesson moves quickly, never allowing pupils to get bored.

“If I just stand up there and say, ‘OK, so here are all the rules of poetry normally,’ no one is thinking,” Carroll later told the SC Daily Gazette.

Carroll stated that the prospect of receiving a bonus at the end of the year is not the driving force behind her desire to be an excellent teacher.

She arrives at school more than an hour before the doors open, rehearses lesson plans with her principal, and printed out the “100%” that hangs over her whiteboard because she sees how intelligent and hardworking her students are, and she wants to help them grow.

Her bonus was a measure of the time and effort she had previously put into her work, she explained. However, the prospect of receiving tens of thousands of dollars in more income serves as an additional incentive for her and other teachers to dig deeper and work better, she added.

“Everyone’s really hungry,” Carroll added. “Everyone wants to succeed for themselves and for the kids. “That is what they deserve.”

Bonuses

Brentwood was one of the first four “schools of innovation” to provide bonuses in 2021. The concept began with Meeting Street Schools, which are community schools that operate as part of a public-private partnership to provide low-income students with the resources they need to succeed.

Since then, the idea has expanded, with 73 schools across the state receiving bonuses through a variety of financing sources.

Ben Navarro, a philanthropist who supports numerous educational programs through Beemok Education, funds the four Meeting Street Schools as well as 22 high-poverty elementary schools in the Charleston County School District.

This includes Brentwood, where more than 87 percent of pupils live in poverty.

Using federal monies, the state Department of Education began giving performance-based bonuses at schools in Allendale and Williamsburg counties that it operates during the 2023-2024 school year. The state’s program expanded to 37 schools last school year, thanks to $5 million in legislative funding, the agency revealed in March.