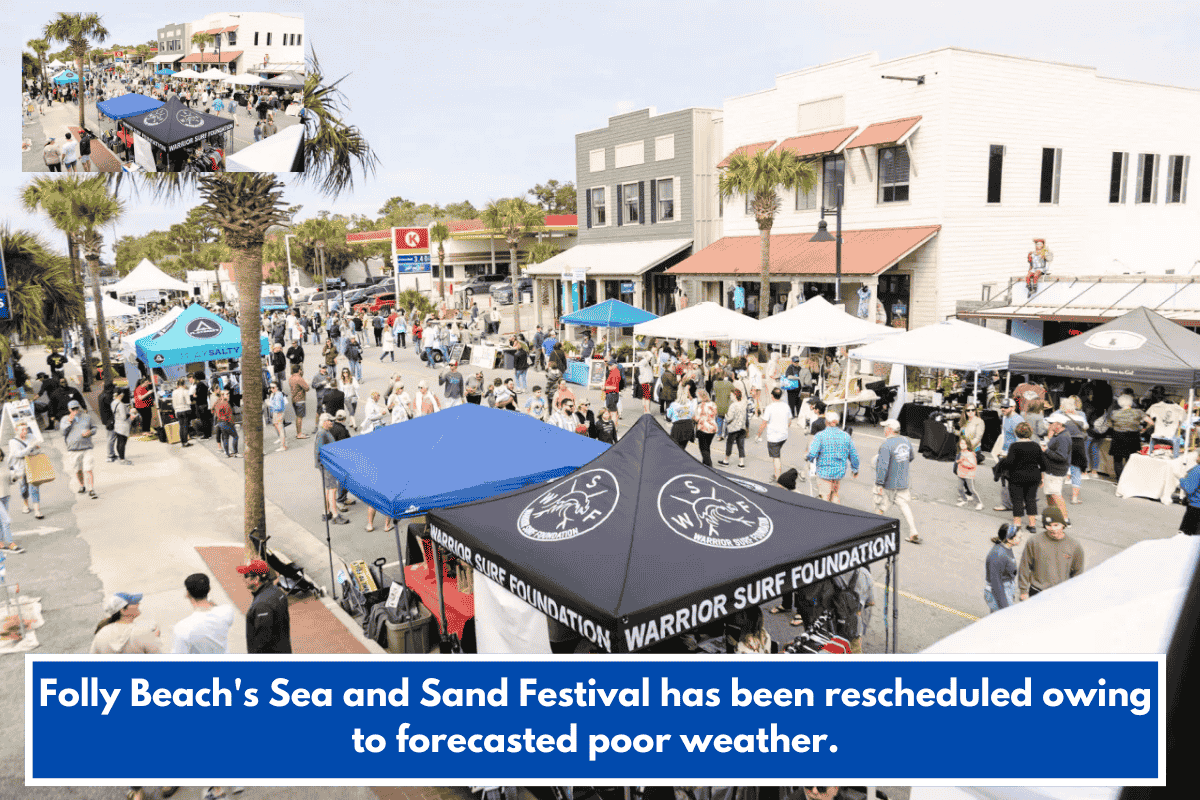

Aerial view of downtown Charleston, South Carolina, which could see a significant coastal resiliency project built to protect against increasing sea levels and declining land mass. Shown on July 28, 2025. (Photo: Jeffrey Basinger/Floodlight)

This post is from Floodlight, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the forces impeding climate action. Sign up for the Floodlight newsletter here.

Luvenia Brown, who lives on a quiet street near the marsh in Charleston’s Rosemont neighborhood, pays more attention to weather reports than she did previously. She has lost lawn mowers, bikes, and outdoor furniture to rising seas that have frequently flooded her yard.

Brown’s home is high, so the water has not entered the interior. Not yet. But she is quite concerned about what the future will hold.

“If the water continues to rise at its current rate, I don’t want to be here,” said Brown, 58, a medical driver. “… I adore my surrounding area. But I believe my life is more essential.

Just a half mile to the south, a large new development is taking shape, with plans for stores, offices, and 4,000 houses. Brown is concerned that all of the additional concrete and pavement may exacerbate floods in her community.

Charleston is one of the nation’s fastest-growing cities, as well as one of the most prone to flooding. As climate change causes sea levels to rise and storms to become more powerful, this historic city has become a warning bell for what is to come along America’s coasts: Some neighborhoods will retreat, others will be preserved, and still others — generally lower-income ones — may be left behind.

In Charleston, these futures are colliding. The city and the federal government are constructing a $1.3 billion seawall to protect the renowned downtown peninsula, which features royal, pre-Civil War houses and majestic moss-covered live oaks.

On September 9, the City Council approved a $2.5 million budget for additional design work and authorized an agreement between the city and the Army Corps of Engineers. According to The Post and Courier, the city will bear $455 million of the overall cost.

However, under present designs, the wall would not extend to lower-income communities such as Rosemont, a historically Black community bounded by a freeway and surrounded by industrial facilities. That might make those families more vulnerable than ever.

“I’ve seen how all those floodwaters demolish people’s houses,” Brown told the crowd. “I don’t think I want to be part of that.”

What is happening in Charleston is being replicated in dozens of coastal towns across the country, including New York and California.

Flooding in the coastal United States is expected to increase tenfold over the next 25 years, owing primarily to sea level rise, according to a recent estimate by the non-profit Climate Central.

Over the next 25 years, the group estimates that 2.5 million Americans will be compelled to relocate.

The rising floods are causing insurance firms to raise premiums and deny policy renewals. A Brookings Institution investigation found that ZIP codes in coastal South Carolina have some of the highest insurance nonrenewal rates. All of this is expected to drive some residents to higher or drier ground.

To understand how Charleston reached this tipping point—and what makes it particularly vulnerable—you must first consider its topography.

Rising water, intensifying crisis

The city was built on marshland and mud flats at the junction of three rivers and the Atlantic Ocean. Flooding was once significantly less common.

However, even an afternoon thunderstorm or an extremely high tide can overwhelm drainage systems and swamp streets.

The issue is not simply more rain, but also increased water levels. The water level in Charleston has risen by around 13 inches during the last century. However, scientists predict that it will accelerate by 2050, rising another 1.2 feet. By the end of the century, the water is predicted to be around 4 feet higher than it is now.

The ground is also sinking.

Charleston is one of the fastest subsiding cities in the United States, owing to groundwater pumping and the settlement of natural sediments and filled marsh areas. Rising seas and sinking land pose a twin threat to the metropolis, increasing its vulnerability to flooding.

According to Climate Central’s Coastal Risk Finder, more than 8,000 people and 4,700 properties in Charleston County may face annual flooding by 2050, even under moderate climate action scenarios. By 2100, more than 60,000 people may be affected.

The Lowcountry, as the region is known, has always been low. But now it’s going lower, wetter, and more difficult to protect.

Meanwhile, rapid expansion is paving over stormwater-absorbing forests and wetlands. Every new development and strip mall replaces absorbent land with impermeable surfaces such as asphalt, rooftops, and parking lots, causing precipitation to flood into areas like Rosemont.

The uneven conflict with the sea

After Hurricane Matthew flooded Charleston’s famed Battery Wall in 2016, then-Mayor John Tecklenburg and other officials sought advice from Dutch flood specialists, hoping to tap into a country known for its skill in seawall construction.

Charleston created a comprehensive water plan to safeguard itself while encouraging sustainable expansion. Federal officials have proposed an 8-mile-long, $1.3 billion seawall to protect the city’s historic peninsula from future storm surges and sea level rise.

The city’s portion is projected to be more than $450 million. Tecklenburg stated that it will not be an easy sell. However, the former mayor believes the option is simple.

He advised Floodlight, “If you give up the peninsula, you might as well head for the hills.”

But neighborhoods like Rosemont, which are just beyond the wall’s reach, will remain exposed. Parts of the neighborhood are expected to be underwater before the end of the century. Some believe the wall may exacerbate flooding in exposed places.

Skip Mikell, a veteran community leader in Union Heights, a historically Black neighborhood, stood at the end of Peace Street in Rosemont, overlooking a neighboring marsh.

“In 70 years, where we are, if nothing is done, it will be water,” Mikell said, adding, “The gentry of Charleston have connections, money, and a voice.” “These communities are voiceless.”

The long road of retreat

A calm swath of weeds, marsh grasses, and black-eyed Susans extends across what was once a neighborhood, some 12 miles northwest of downtown Charleston. Bridge Pointe was previously a small community of 32 townhouses.

The property was given to nature after the city and federal governments paid off its flood-weary residents. However, the process was sluggish and cumbersome, as is common with buyouts across the country.

John Knipper was among those relocated. He moved from New York to Charleston in early 2015, having recently retired, and purchased a three-bedroom townhome in Bridge Pointe for $172,000.

However, just six months after he moved in, an August thunderstorm transformed a neighboring brook into a river. Several inches of water seeped into his living room. Then, in October 2015, a stalled weather system dropped more than 15 inches of rain throughout the region. His first level was submerged by 2 ½ feet of water.

The storms and floods continued for several years. In 2017, FEMA approved a $10 million buyout for Bridge Pointe residents and their neighbors. It had flooded four times by then, according to Knipper, leaving the homes “really unsellable.”

Residents did not get relocation funds until nearly four years after buyout conversations began. The Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that a typical buyout can take more than five years.

Meanwhile, the United States Government Accountability Office discovered that there is no national policy in place to relocate people from flood-prone locations.

Building toward disaster

Many additional residences will be built within a mile.

Long Savannah, a big new development, is projected to have up to 4,500 residences. It is one of several high-profile projects underway in flood-prone areas of Charleston County.

Long Savannah, like other megadevelopments proposed for Charleston, is expected to harm wetlands, which act as natural sponges, absorbing up rain and slowly releasing it to keep floods under control.

Other big developments in the works include Magnolia Landing, a 4,000-home project near the Rosemont community, and Cainhoy, a 9,000-home development that would fill marshes on a low-lying peninsula near Charleston where flooding is already a concern.

“Charleston has a history of building in repetitively flooded areas,” said Robby Maynor, a climate campaign associate with the Southern Environmental Law Center, which sued to conserve portions of the wetlands in the Long Savannah development. “We absolutely must stop building in low-lying and flood-prone areas to avoid making an already difficult situation even worse.”

According to Charleston municipal officials, new buildings in flood-prone locations must now include flood defenses such as higher elevation standards and improved drainage systems. However, scientists and residents argue whether those precautions are sufficient, or whether developing in hazardous locations simply shifts the risk to others.

“A similar story is playing out in cities all across the United States,” according to NASA’s Earth Observatory, “but the Charleston area stands out in one critical way — much of the new development has happened on low-lying land that is especially vulnerable to sea level rise and flooding.”

When leaving is not an option.

Ana Zimmerman and her husband purchased their modest, one-story home on Shoreham Road in 2005, as part of a close-knit neighborhood where neighbors cared for each other’s children.

The first signs of problems appeared early one morning in October 2015. It was still dark when she placed her feet on the bedroom floor, water lapping at her ankles. A tremendous storm has overtaken the street.

Zimmerman rushed to save photo books and family cats, but the house sustained more than $80,000 in damage.

The Zimmermans repaired their home using the insurance settlement and their own labor.

However, when Tropical Storm Irma hit two years later, Zimmerman recalls hearing neighbors screaming as 7 inches of floodwater surged into her home, causing it to be declared a total loss.

Eventually, the couple abandoned the flood-damaged property and allowed it to go into foreclosure, walking away from 12 years of equity.

They now live close in a house with an elevated foundation. Zimmerman, who describes herself as a “unintentional flood activist,” has lobbied public officials for stronger building codes and more transparent flood-risk declarations.

She describes her experience as a “canary in a coal mine” for other low-lying coastal villages.

“Entire neighborhoods will have to move,” said Zimmerman, a college biology professor. “But the vulnerable among us, there will be no one there to help them, save them, and they will not be able to save themselves.”