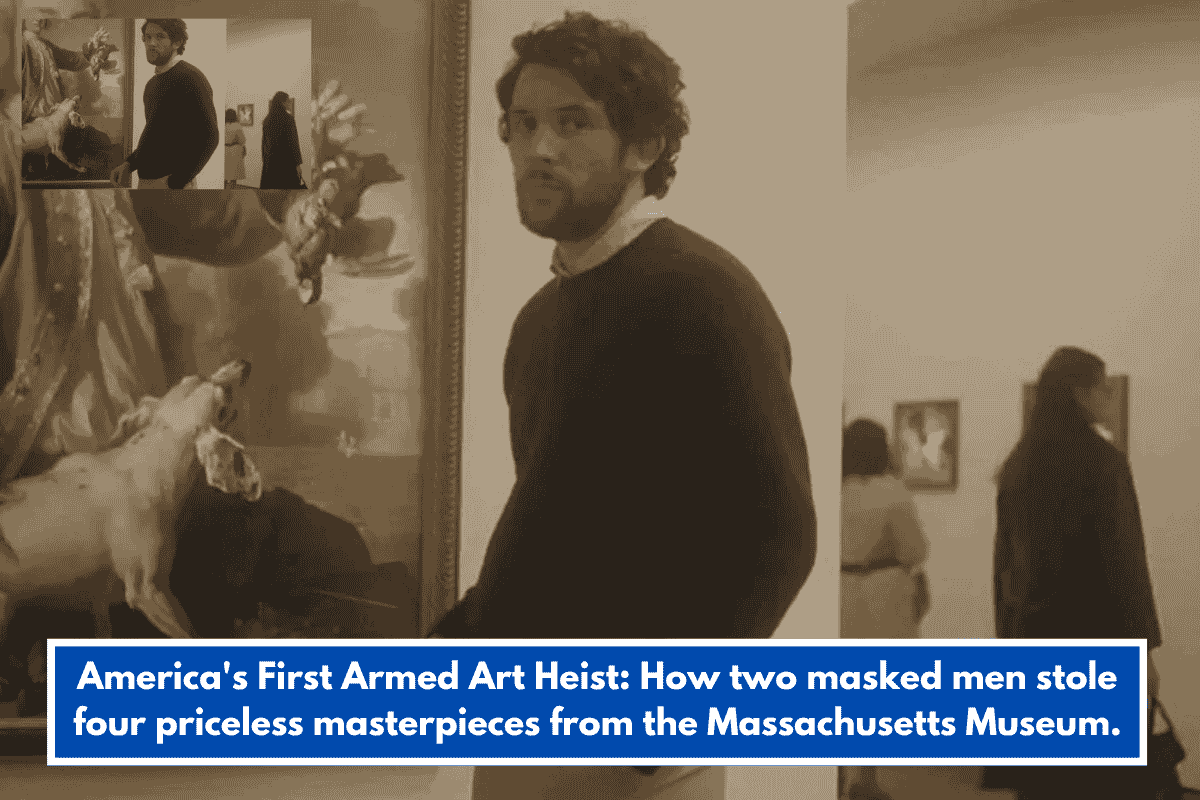

Some feel that the contemporary age of American art heists began on May 17, 1972.

That was the day two masked men entered the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts with a gun and left with four masterpieces.

The theft lasted about five minutes and was practically incident-free until the museum’s unarmed security guard attempted to halt and question the two men who were running towards the exit.

Philip Evans, the security guard at the time, was 57 years old and told the Telegram & Gazette in 1982 that he initially stopped the guys because they were rushing across the museum’s 1,700-year-old Antioch mosaic on the ground floor.

“Get out of the way!” “We’re going through,” the first masked robber allegedly stated as Evans attempted to grab him.

Evans claimed he was swatted by the paintings that guy was carrying, but he managed to wrap his arms around the second robber’s neck. Then he heard a gunshot as both men got into a waiting car and sped away from the area.

Police quickly arrived on the scene, followed by FBI agents and customs officials.

Evans, who had been wounded in the waist, was taken to a local hospital and treated for what physicians later described as a minor wound.

Investigators began questioning eyewitnesses and museum officials at the scene, and discovered that the robbers had stolen a Picasso, two Gauguins, and a painting ascribed to Rembrandt. (It is now thought that the piece was painted by one of the artist’s students.)

Among the eyewitnesses were four high school students who were working on a project at the time, two of whom were in the room when the bandits stole the paintings.

Beth Ellen T. Hurowitz and Kathy Kartiganer were about to enter one of the galleries when one of the masked guys saw them and instructed them to get on the floor, pointing his rifle at them.

“We kept our heads down and said stupid things like ‘We can’t see you.'” “We’re not looking at you,” Kartiganer stated in a 2022 interview with the Telegram & Gazette. “I remember shivering, feeling like I was about to soil my trousers. “I am surprised I didn’t.”

According to the two teenagers, the men then went about their job, collecting “The Brooding Woman” and “Head of a Woman” by Paul Gauguin, “Mother and Child” by Pablo Picasso, and “Saint Bartholomew,” which was credited to the Dutch painter Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn at the time.

“We observed these two people go from room to room, taking certain paintings. “They were not arbitrary in what they took,” Hurowitz stated.

Outside, the ladies’ two friends were waiting in a parked car and had their own encounter with the masked burglars when they accidentally blocked the getaway car.

“So, while we’re waiting, I see two men run out with paintings,” Geri Wolfson said in a 2022 interview with the Telegram and Gazette. “The drawings were in these large pillowcases. They throw them into the car. “One, they installed on the roof.”

The men then pushed a gun in Wolfson’s face and forced her to move the car.

“I’d never seen a gun before,” Wolfson explained. “So I moved. I swiftly reversed and pulled back onto Lancaster Street, and the [getaway] automobile sped out of the art gallery.

When police discovered the getaway automobile abandoned less than a mile away on the Worcester Polytechnic Institute campus, they realized it had been stolen the day before.

It took police only 10 days to arrest four persons for their roles in the crime, due in large part to information from local bar patrons who reported that the thieves had been bragging about their accomplishment.

On May 20, 1972, the New York Times reported that police had arrested William Carlson, 25, and Carol Naster, 28, for their roles in the crime. Carlson was one of the masked thieves, while Naster, who was not present at the museum during the incident, was charged of being an accessory.

According to the publication, two additional guys were detained the next day: masked robber Stephen A. Thoren, 30, and getaway driver David Aquafresca, 22.

The artworks were eventually discovered buried on a pig farm in Rhode Island and returned to the museum in June, a little more than a month after they had been stolen.

Officials had yet to apprehend the mastermind behind the operation, and the search for Florian “Al” Monday would continue for another year before he was apprehended in Montreal and sent back to the United States to serve a nine-year sentence.

The Worcester Art Museum heist was quickly forgotten, but it is now being addressed again as a result of Kelly Reichardt’s new film, which also features Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, and Showing Up.

The film The Mastermind, based on the 1972 burglary at the Worcester Art Museum, stars Josh O’Connor as the aimless son of wealthy parents who plans to steal a historic piece of art from a local museum.

The film, much like the real-life heist, emphasizes the one aspect of the robbery that remains unexplained:

Why?

According to The Times, the stolen pieces were so well-known that the burglars would not have been able to sell them on the open market, leaving the group with four paintings worth more than $1 million (at the time) that they were unable to sell.

Monday, the mastermind behind the 1972 robbery, subsequently claimed it was all for the sake of owning his own Rembrandt, which turned out to be the work of a disciple of the Dutch master.