MOUNT PLEASANT, S.C. — A White House-ordered study of Smithsonian museums may result in the elimination of a Lowcountry sweetgrass basket maker’s work.

The internal examination aims to eliminate material the Trump administration views “divisive.” The study will include a visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where two of Corey Alston’s baskets are now on display.

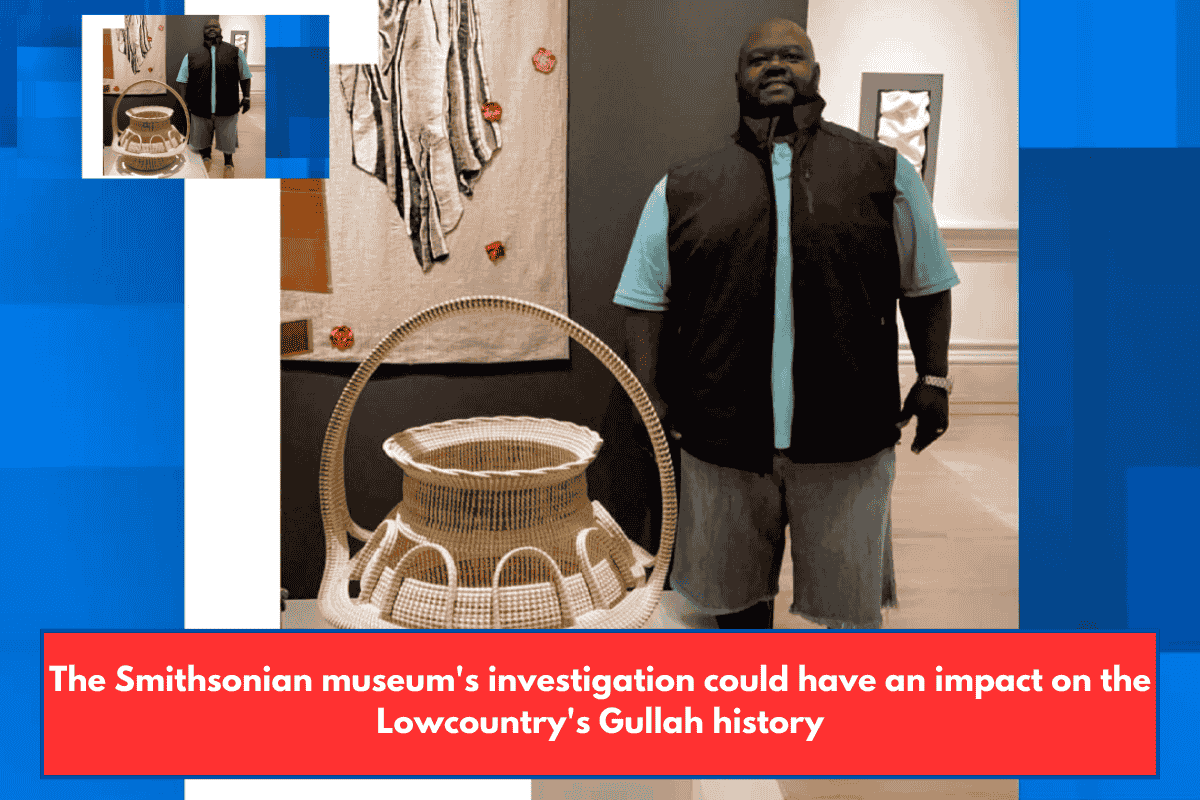

Alston, a Mount Pleasant native, has been documenting his ancestry for 22 years.

Sweetgrass baskets are handwoven houseworking instruments made by stitching four natural grasses: pine needle, palmetto, bulrush, and sweetgrass. It is an art form that has only existed on the Carolina coast for almost 300 years.

“Every little community is known for something. You have cast-net manufacturing, canoe making, storytelling, spices and cooking, religion and language… we’re part of the weaving side of ourselves,” Alston explained.

This tradition dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries, when thousands of Africans from the Windward Coast, Gold Coast, and Rice Coast of West Africa were forced to the shores of the New World, specifically the Colony of Carolina, due to their brilliance and knowledge of rice cultivation.

“Throwing the raw rice in the air with this tool was a way of threshing or cleaning the raw rice,” Alston told me. “The rice became such a crop, it made Charleston one of the richest cities for 90 plus years off of the back of the enslaved.”

Language, food, religion, and even medicinal traditions all came with them, wrapped and anchored in African heritage that we now refer to as Gullah Geechee culture.

“In 2006, the United States Congress recognized this cultural identity here and they established what we know today as the Gullah Geechee Culture Heritage Corridor, which extends all the way from Wilmington, North Carolina, all the way down to Saint Augustine, Florida,” Michael Allen, a former employee of the National Park Service, explained.

Allen, a historian, acknowledges that our society is currently in the midst of a discussion about history and culture. He believes that all voices and stories should be heard and included in the American experience.

“There’s a resiliency, I guess, in the whole culture dynamics of willing to step forth to preserve, to protect and to sustain and to maintain this part of our cultural integrity,” Allen told me.

In March, President Donald Trump issued an executive order directing an internal examination of select Smithsonian museums to ensure that no “divisive or race-centered ideology” exists. The administration intends to begin by focusing on eight museums, including the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It’s a great joy to be able to display our artwork at museum levels because it tells a story of our ancestry,” Alston told me. “It keeps everything going. This is a discussion starter for individuals who have never heard of the Gullah people.

Alston expressed sadness over the possibility of removing certain pieces from the Smithsonian. He feels that deleting history would help strengthen America.

“You see a large piece at a museum in another state or city, and you want to know who these folks are. Who are these people who make art out of marsh grass? And it will reverberate throughout the Gullah community,” Alston stated.

Highway 17 in Mount Pleasant, commonly known as Sweetgrass Basket Makers Highway, has sweetgrass basket stands at almost every crossroads. That is because the Town of Mount Pleasant is the foundation for the preservation and practice of Gullah sweetgrass basket manufacturing.

“I am extremely proud to see the stands up and down Highway 17, because there’s no other town in America that has them,” Alston told the crowd.

He described it as a community dedicated to preserve the original stands where anyone could and still may purchase a magnificent Charleston relic of the Gullah lineage, which is still flowing and growing from the center.